Event Date

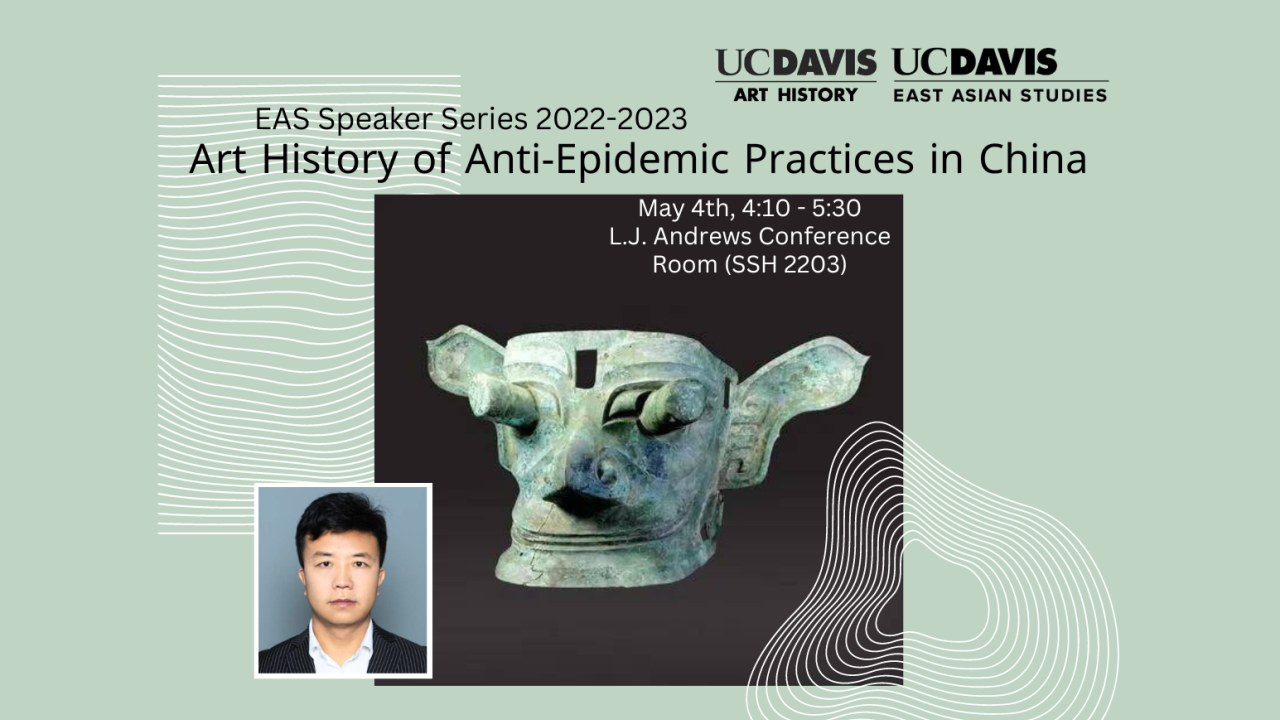

We mainly understand the history of China’s anti-epidemic practices in East Asia through the discipline of art history. We found five forms of anti-epidemic practices: first, the way to create Fang Xiang Shi’s God in ancient China; second, AiYe (Artemisia argyi) hung from the door to clear the air of viruses in homes and people; third, the way of “colorful silk is tied to the arm” at the turn of spring and summer; fourth, the way of Bronze drum driving away the epidemic in the Qing Dynasty; fifth, the modern scientific method of Dr. Wu, etc.

The above ways are what we found through researching art history in China, which documents the traditions used in attempts to drive away disease; these illustrations provide anthropological evidence about people’s belief systems at the time. Two conclusions can be drawn: they show that Chinese art has always paid attention to sociological issues, and it shows a transformation process in Chinese art through history “from god to person” or “folk beliefs to scientific method.” In addition, we found the close relationship between folk art and elite art in China through the study.

In studies of the visual arts of China, themes of auspicious tidings or events have dominated art historical research; such inauspicious topics as epidemics and disasters have rarely been the focus. The outbreak of COVID-19, however, brought sudden awareness to these overlooked topics such that scholars are now looking at historical sources for evidence of records of earlier epidemics and disasters. This talk identifies depictions of diverse ways that people handled these topics, and explains how throughout time China’s people used social, cultural, and increasingly scientific practices to ward off disease. In doing so, this project brings old topics into new focus for China’s cultural and visual history.

Junping Liu is a UC Davis Visiting Scholar at the Department of Art and Art History and a Professor of Art History at the School of Art & Design, University of Emergency Management.